by D.E. Powell

People have turned to George Orwell’s 1984 and Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale, writers who “talk truth to power” and have both the breadth of craft and clarity of vision to deliver the hard lessons—for wisdom and resistance—in light of the recent political turmoil following the Trump presidency. I myself have turned to Albert Camus. However, there is one other writer who belongs on that place of honor for the aptness of her prophecies, gifts as a storyteller, and the clear and unwavering voice in which she names the ugly aspects of the American soul.

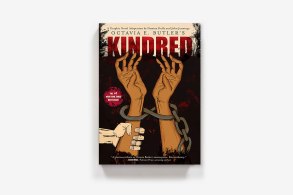

Octavia Butler was a black feminist fantasist and former factory assembly line worker who died in 2006 at the age of 58, whose body of work resonates more with the passing of time. For those who want to give her work a try, the creative team of Damian Duffy and illustrator John Jennings has adapted Kindred, Butler’s 1979 classic, into a handsome, hard-hitting graphic novel.

Kindred is the story of Dana, a young African-American woman living in 1970s Los Angeles who time-travels to a pre-Civil War plantation in Maryland. There Dana encounters a young white boy named Rufus, whom she saves from drowning. Dana returns to her own time where she lets Kevin, her Caucasian husband, know what happened. Kevin is supportive of Dana but not sure what to think. Dana continues to hop between past and present, being called back whenever Rufus is in danger and needs to be saved. This is more than an act of compassion; Dana has discovered that Rufus is her ancestor, and her failure to save him means she will never be born. Kevin is pulled over with her during one; he too endures the horrors of slave era America, albeit as a white man with its attendant privileges. Dana and Kevin must hide the nature of their relationship in order to survive, but they are separated and Dana returns to the present without Kevin. When Dana time-travels to the past to save Rufus, she also struggles to reunite with Kevin, who has moved north. During the course of the story, both are infected in different ways by the soul-corroding effects of slavery (especially Dana who must wrestle again and again with saving the increasingly malignant Rufus), warped and wounded into new forms that they will carry until their dying days.

Duffy and Jennings, whose previous works have addressed underrepresentation in comics culture (Out of Sequence: Underrepresented Voices in American Comics, Black Comix: African American Independent Comics, Art and Culture) do so much right with their adaptation. Duffy has chiseled the novel down just ever so slightly, and it moves crisply along, with the strengths of a great movie adaptation and with Butler’s complex ideas and wise takes on how the evil of slavery is hard-coded in the American soul to our eternal shame and danger. Jennings’ art adds immediacy and intimacy to the proceedings, capturing both tender moments and unspeakable suffering with precision and grace. The daily fear, random violence and heart-rending separations of families and friends are almost physically painful in this graphic format. I am convinced Butler would have loved this adaption. Duffy, Jennings and the folks at Abrams have created a great graphic novel that stands on its own merits and that also introduces a critical voice to a new generation. They should be damn proud of this adaption.